This biographical sketch of Ida R. Cummings first appeared on the Online Biographical Dictionary of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the United States and appears here by courtesy of the publisher, Alexander Street.

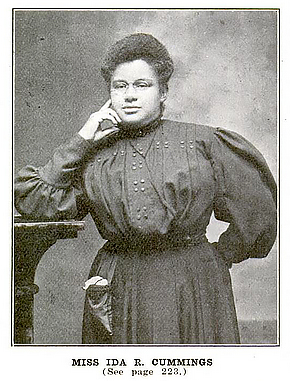

Biography of Ida R. Cummings, 1868-1958

By Elizabeth A. Novara, PhD Student, University of Maryland

Pioneering kindergarten teacher, community leader and dedicated activist for children

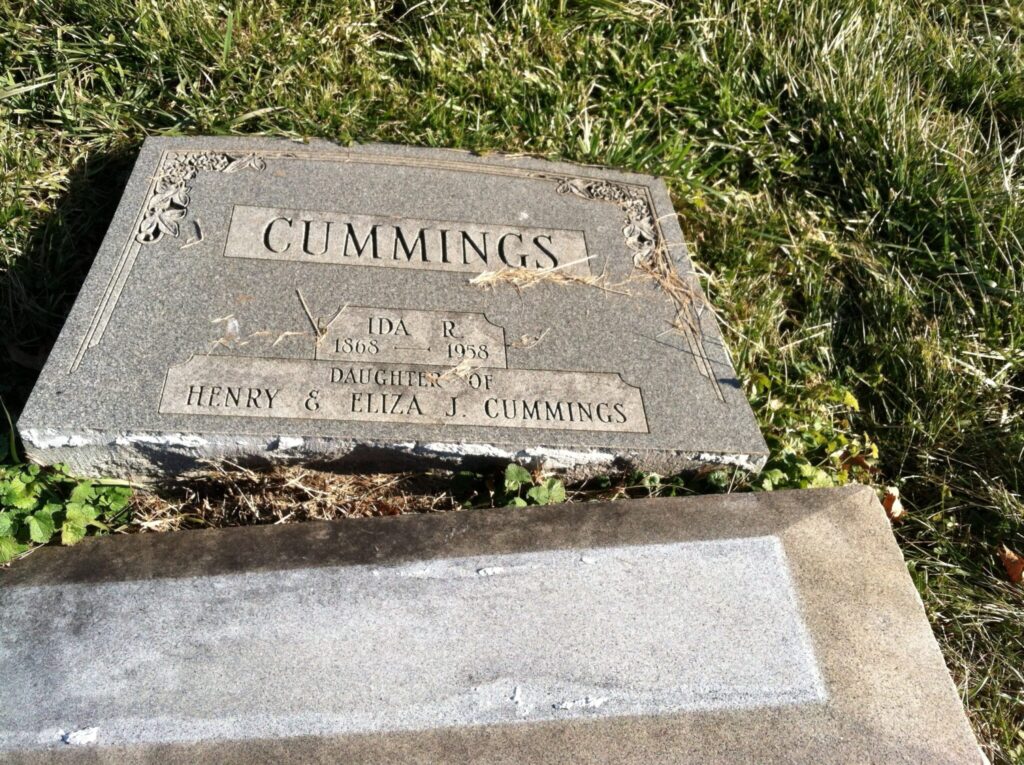

Ida Rebecca Cummings was born on March 17, c.1868, in Baltimore, Maryland. She was the daughter of Eliza J. Cummings (1843-1913) and Henry Cummings (1828-1906). Her mother’s parents, Sidney Hall Davage (c.1816-1896) and Charles Davage, had lived in Baltimore since before the American Civil War. Sidney had been a slave in Baltimore County and was manumitted before Eliza was born. Ida’s father, Henry, was a well-known cook for various restaurants and caterers in Baltimore, and her mother, Eliza, ran a boarding house at one time and was recognized for her involvement in community affairs, including political organizing and charitable efforts. Ida had four brothers and one sister: Harry S. Cummings (1866-1917), the first African American Baltimore City Councilman; Aaron M. Cummings; William O. Cummings; Rev. Charles Gilmore Cummings; and Estelle Cummings Fennell (Mrs. Joseph F. Fennell).

Ida attended the school of the Oblate Sisters of Providence, an order of African American sisters, like her mother before her, and the public schools of Baltimore. She was a graduate and post-graduate of the Baltimore Kindergarten Training School Association. During her summers, she took additional courses at various institutions including, the Chicago Kindergarten College, Hampton Institute, and Columbia University. She also had the opportunity to travel and study urban kindergarten programs in the North and in the West. Ida received an A. B. degree from Morgan College in 1922. She later served as the only woman on the board of trustees of Morgan College and also became a trustee of Bennett College for Women in Greensboro, North Carolina.

As early as 1895, Ida began her career as an educator in the public schools of Baltimore, teaching primary school at Sparrows Point. In 1901, she was appointed as appointed as the first African American kindergarten teacher in the Maryland public school system and eventually became “directress” of public school no. 112, the largest colored public school in Baltimore at the time. Ida worked at school no. 112 for many years, but she later transferred to school no. 122. She retired from teaching in 1937.

Family, church, and community all held important places in Ida’s life. Ida’s mother, Eliza, had actively supported her local church, Morgan College, and was deeply involved in political and civic activism in Baltimore’s black community. Ida advocated for many of the same causes as her mother, with an interest in assisting children and families. She worked to support black community interests on the local, state, and national levels.

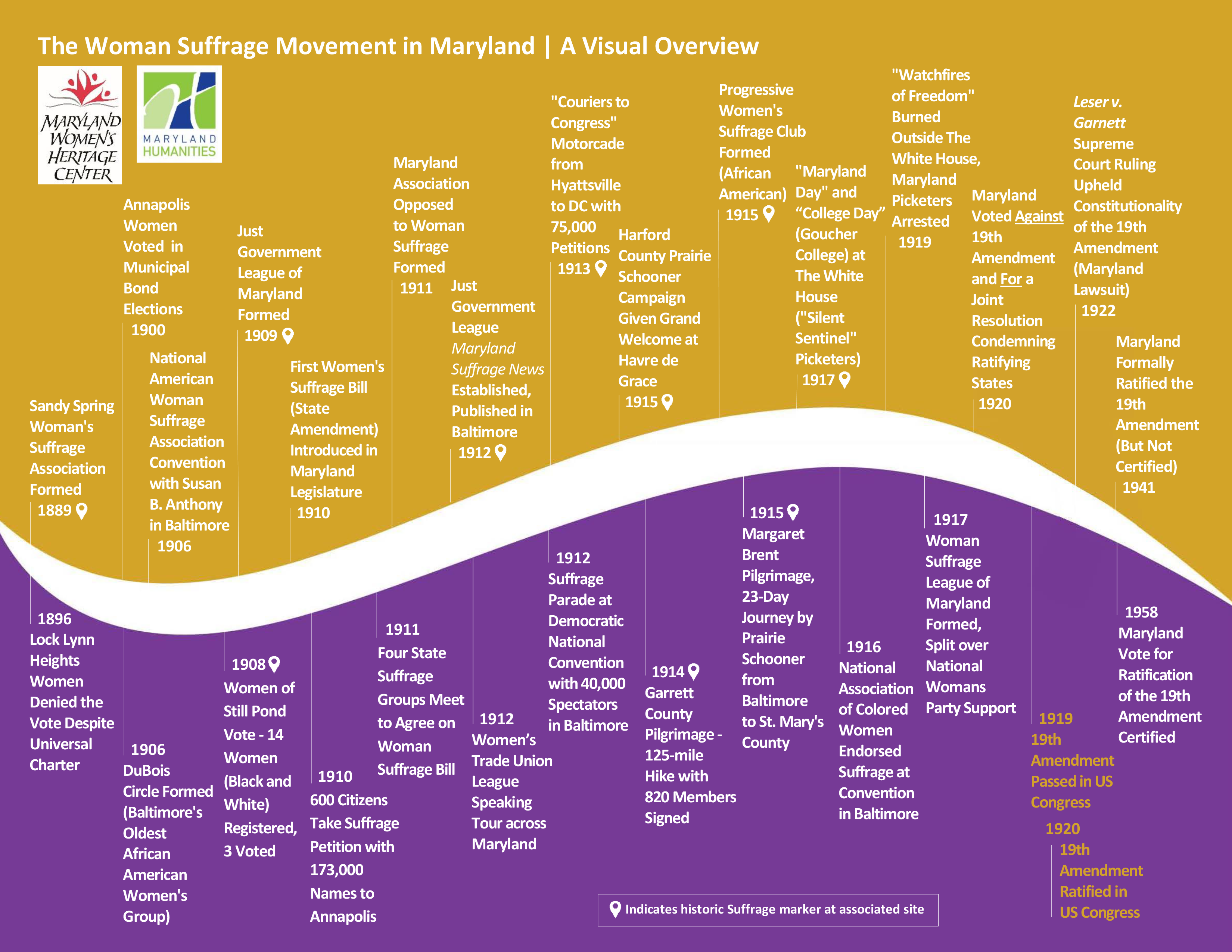

Much of Ida’s activism was rooted in the Metropolitan M.E. Church of Baltimore. She served as superintendent of the primary department of the Sunday School and superintendent of the Hattie A. Johnson Chapter Junior League. She was also the Junior League Superintendent of the Baltimore District of the Washington Conference and Junior League superintendent and organizer of the Federation of Epworth Leagues, the young adult association within the M.E. Church. In 1910, Ida published an essay in the book Methodism and the Negro entitled “How Can We Best Utilize the Young People in the Interest of Home Missions and Church Extension?” She served as vice president of the Maryland Federation of Christian Women in 1915 and Estelle Hall Young, the president of the Colored Women’s Suffrage Club served as recording secretary alongside her. The Maryland Federation of Christian Women went on record as being in favor of women’s suffrage in 1915. Like her mother, Ida was a member of the Women’s Home Missionary Society, and in 1920, she was elected delegate of the M.E. General Conference.

In 1904, Ida, her mother, and other women of the (Colored) Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) organized the Empty Stocking Club and Fresh Air Circle, a charitable group affiliated with the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). Headquartered at the YWCA, this charity provided clothing and other necessities to black families. In 1907, the group aided over 1,000 children by giving out Christmas stockings and gifts. In addition, they purchased a farm in the countryside in Delight, Maryland, and sent children there each week during the summer to escape the hot city and provide them with the experience of fresh air, healthy food, and exercise. The establishment of Empty Stocking Club and Fresh Air Circle was one of Ida’s major achievements, and she served as president of the group for many years. She was often credited for her fundraising for charity, including organizing a block party on the 1200 block of Druid Hill Avenue.

Heavily involved in the NACW, Ida held national office in the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, serving as corresponding secretary for two terms (1910-1914). She was elected vice president in 1916. It was also through the NACW that Ida supported issues such as women’s suffrage, temperance, and anti-lynching and moved in circles with prominent black women leaders such as Mary Church Terrell, Hallie Quinn Brown, Margaret Murray Washington, and Mary McLeod Bethune. A special women’s suffrage issue of The Crisis, the national publication of the NAACP, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois, identified Ida as one of several prominent “suffrage workers” within the NACW. Ida delivered addresses and reports at NACW conferences and was the chairman of the local arrangements committee for the annual conference in Baltimore in 1916.

During World War I, Ida was appointed by Maryland Governor Emerson Harrington as chairman of the Colored Woman’s Section of the Council of National Defense. She gave speeches at mass meetings with the governor and other state and community leaders in support of the war effort. Never flagging in her political activism, she served as President of the Woman’s Campaign Bureau of the Colored Republican Voters’ League in the 1930s, and in 1940 was a presidential elector to the Republican National Convention. Ida was a member of the executive board of the Francis Ellen Watkins Harper Grand Temple, Daughter of Elks, served as grand assistant recording secretary, and was elected daughter ruler in 1926. She also held a membership in the Order of the Eastern Star.

Ida R. Cummings died on November 8, 1958, at her home at 1234 Druid Hill Avenue, which had been purchased by her parents circa 1900, and is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Baltimore. For much of her life, Ida had lived in the family row house on Druid Hill Avenue, a thriving a center of community life in black Baltimore at the turn of the twentieth century. Various family members cohabitated in this house and came and went over the years. Always concerned with children and their welfare, Ida not only assisted children in the community, but served as a “foster mother” to nieces and nephews who lived in her home at various times.

Sources

Chapelle, Suzanne Ellery, and Glenn O Phillips. “Ida Rebecca Cummings.” In AfricanAmerican Leaders of Maryland: A Portrait Gallery, 70-71. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 2004

Cummings, Ida R. “How Can We Best Utilize the Young People in the Interest of HomeMissions and Church Extension?” In Methodism and the Negro, edited by I. L. Thomas, 233-238. New York: Eaton & Mains, 1910.

“The Cummings Family: Piecing A Family Back Together,” March 27, 2019, (last accessed June 17, 2019) https://www.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=706f1755cdbc445383ab857a159c21ed

Hollie, Donna. “Ida Rebecca Cummings.” In Black Women in America: An HistoricalEncyclopedia, edited by Darlene Clark Hine, Elsa Barkley Brown, and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, 291-292. Brooklyn, New York.: Carlson Publishing, 1993

Hopkins, John W. “Remembering the Story of the Freedom House,” Baltimore Heritage,November 13, 2015 (last accessed June 17, 2019), https://baltimoreheritage.org/preservation/remembering-the-story-of-the-freedom-house/

Lockbeam, Kaili. “A Closer Look at the Lewis Collection: Educator & Clubwoman, Ida R.Cummings,” Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture Blog, March 1, 2019 (last accessed June 17, 2019). This website has an excellent photo of Cummings and a thorough biographical sketch. Seehttps://lewismuseum.org/idacummings/

Neverdon-Morton, Cynthia. Afro-American Women of the South and the Advancement of theRace, 1895-1925.Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1989.

Articles within the Afro-American Ledger, later the BaltimoreAfro-American, and other periodicals and directories mention Ida R. Cummings and members of her family. Below is a selection of some of the most useful articles in chronological order:

“Empty Stocking and Fresh Air Circles,” Baltimore Afro-American Ledger, December 9, 1905.

“The Federation of Colored Epworth Leagues in Baltimore,” The Epworth Herald 18, no. 10(August 3, 1907): 239-240.

“Women’s Work for the Race, National Association of Colored Womens Clubs Hold BiennialMeeting in Brooklyn,” Baltimore Afro-American Ledger, August 29, 1908.

“Suffrage Workers,” The Crisis 4, no. 5 (September 1912): 223 and 242.

“Death of an Estimable Woman,” Baltimore Afro-American Ledger, May 31, 1913.

“Women Hold Annual Session,” Baltimore Afro-American Ledger, Baltimore, November 6,1915.

“Baltimore Preparing to Entertain Women’s Clubs,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 22, 1916.

“Four Hundred Delegates Attend National Asso. of Colored Women,” Baltimore Afro-American,August 12, 1916.

“Teacher and Fraternal Worker Calls Fresh Air Farm Her Hobby,” Baltimore Afro-American,August 9, 1930.

“Republicans Appoint Miss Cummings,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 15, 1940.

“Miss Cummings, Elk leader, dies,” Baltimore Afro-American, November 15, 1958.

“Aunt Ida Sleeps Away…,” Baltimore Afro-American, November 22, 1958.