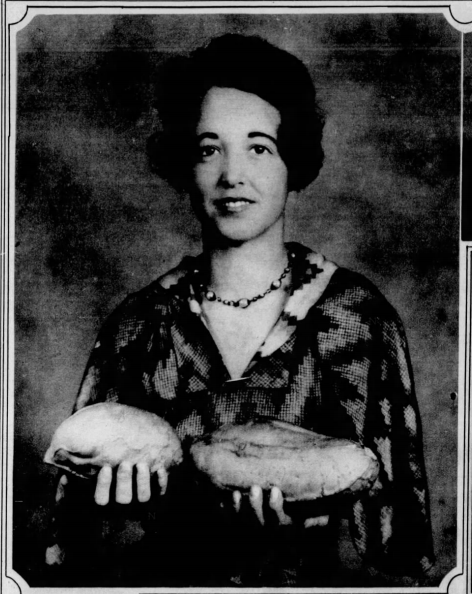

Almira Hood Sweeten

November 1863 – March 24, 1949

By Amy Rosenkrans, PhD

Almira Hood was born in Howard County Maryland in 1863. She married William Sweeten and was widowed sometime before 1892. The couple had one son, George.

In 1892 Almira inherited property and after getting it “in order,” rented it out “advantageously.” That experience motivated her to take up real estate. Although it was not a typical field for women, Almira maintained a successful business in Baltimore for more than 20 years.

Almira attributed her success to the fact that she WAS a woman. In a 1916 Baltimore Sun interview, she posited that women were more successful in business because they were not expected to spend money entertaining male clients and they were more reliable because they didn’t have “petty vices.”

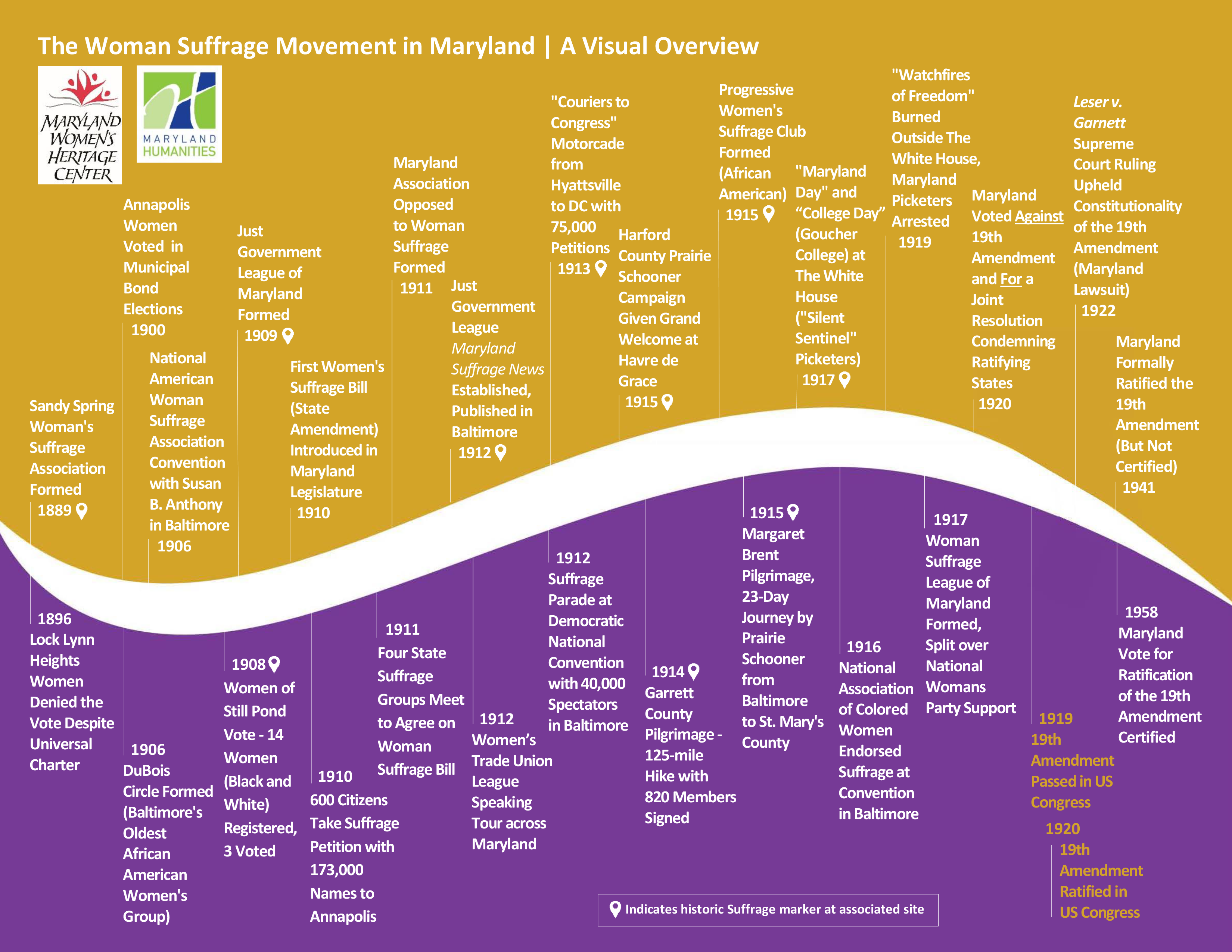

In addition to maintaining a real estate business, Almira was, as the Baltimore Sun called her, an “ardent suffragist.” She played prominent roles in both the Just Government League (JGL) of Maryland and the Howard County Just Government League.

Almira participated in local events like poll watching and hosted events at her home as well as large national events.

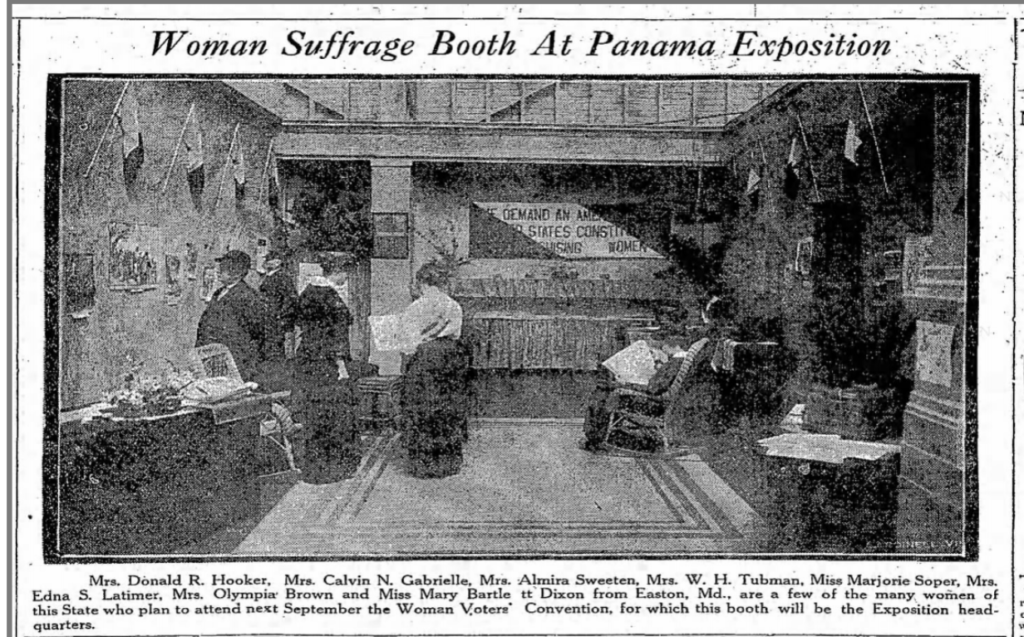

In January 1915, she led the Maryland deputation to the White House where they implored President Wilson to support the Suffrage Amendment. Later that year, she travelled to San Francisco where she represented Maryland at both the Panama-Pacific Exposition and the Woman Voters’ Convention.

Almira also coordinated transportation for Marylanders to Chicago for the suffrage parade that coincided with the 1916 Republican National Convention.

In 1917, she picketed the White House with a delegation of 12 other Baltimore women. Almira was also an integral part of the unsuccessful attempt to convince Maryland legislators to ratify the 19th Amendment.

Almira continued to be active in the women’s movement after the ratification of the 19th Amendment. She was a JGL lobbyist to the Maryland General Assembly for what some considered a radical equal rights campaign, which included provisions that would allow women to retain their own names after marriage and the right to serve on juries. Frustrated and discouraged by the failure of either party to support their ideas, Almira and her colleagues threatened to form a Maryland Woman’s Party.

Unfortunately, Almira’s prediction that Maryland legislators would approve equal rights legislation within two years did not come to fruition. She was still fighting 10 years later when she lobbied Harford County legislator Mary Risteau for her support in legislation that would allow women to serve on juries. Miss Risteau had already voted in two previous legislative sessions against the law and told Almira and her colleagues that she would do so again that year. The legislation did not pass that year. In fact, Maryland women would not be allowed to serve on juries until 1947.

Almira lived just long enough to see women achieve that privilege. She died March 24, 1949 and was laid to rest at the Melville United Methodist Cemetery in Elkridge, Maryland.

Sources:

Local Suffs to Protest, The Baltimore Sun, September 1, 1917

Suffragists Plan New Thrust at Congress, Passaic Daily News, September 14, 1915

Suffs are Planning Their Fall Campaign, The Evening Sun, September 5, 1919

The Deputation to President Wilson, Maryland Suffrage News, January 2, 1915

Wilson Fails Silent Thirteen, The Baltimore Sun, January 19, 1917

Women in Maryland Threaten New Party, The Western Sentinel, February 28, 1922

Women in Real Estate, The Baltimore Sun, May 28, 1916

Women Jury Lobby Hits Snag in Miss Risteau of Harford, The Baltimore Sun, January 22, 1931

Women Lobbyists Find Scant Encouragement, The Baltimore Sun, February 2, 1922