Gladys Carolyn Greiner

By Jean Baker

Gladys Carolyn Greiner was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1890, the daughter of civil engineer John Greiner. Her mother, from a well-known Virginia family, was a proud member of the Daughters of the American Revolution who expected her eldest daughter to participate in Baltimore’s social life.

Carolyn Greiner attended the National Park Seminary in Forest Glen, Maryland and graduated from the Baldwin School in Philadelphia. Greiner made her debut at Baltimore’s Bachelor’s Cotillon, and joined her parents and sister on a European tour, a familiar experience for upper-class young women. But Greiner had other things on her mind, trivializing the life of socialites in the poems she liked to write: “From party to party we go/Each trying to make the greater show/Taking on subjects we do not know.”

During her twenties, Greiner taught at a settlement school in Kentucky; took a summer program at Harvard that focused on children’s playgrounds, and taught French classes at Baltimore’s Mount Royal School. But it was suffrage work that came to dominate her activities. In 1917 she joined Alice Paul’s National Womans Party, becoming one of its most fearless activists.

On June 25,1917 Greiner carried the suffrage banner from headquarters on Lafayette Square to the gates of the White House. Emblazoned with the suffrage colors of purple, white, and gold, it read “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?” Greiner was seized by a policeman and assaulted by onlookers who tore the banner from her. Along with other members of the NWP Party, she was arrested. Given the choice of paying a fine or going to jail, she chose jail. Greiner was imprisoned three more times.

In August 1918 she was arrested along with Alice Paul. Sentenced to thirty days in jail, she was released the day before she began a hunger strike. As she informed a reporter, in prison she was denied even the privileges of criminal prisoners. “They put me in solitary confinement because I broke a window to get some fresh air.” Undeterred, a few months later she was among the women who burned President Wilson’s effigy and were sent to prison.

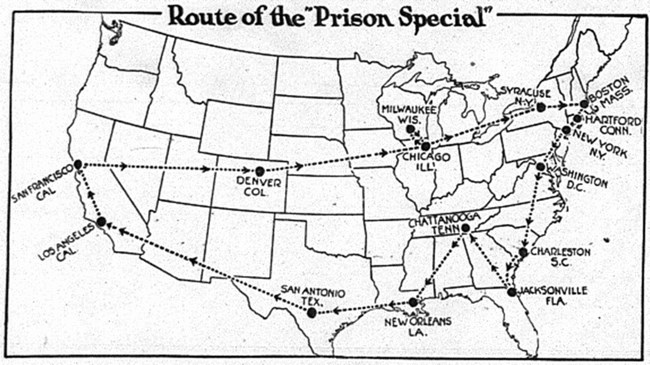

Released from prison, Greiner joined members of the NWP picketing the Senate in October 1918. Again she was arrested trying to take the suffrage colors into the Capitol. In 1919 wearing her prison uniform she joined other women on the Prison Special, a nationwide railroad tour intended to publicize the movement during the fight to ratify the 19th Amendment. After ratification Greiner served as the treasurer of the NWP.

Greiner was as well a Maryland state champion in golf. She died at her home in Baltimore in 1961, having represented in her early years the activist wing of the suffrage movement.

Bibliography: articles in the Baltimore Sun, Inez Haynes Irwin, The Story of the Woman’s Party, Margie Luckett, Ed.

Maryland Women, Online Biographical Dictionary of Militant Women Suffragists

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

This biographical sketch first appeared on the Online Biographical Dictionary of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the United States and appears here by courtesy of the publisher, Alexander Street.

Born in September 1890 in Baltimore, Maryland, Gladys Greiner was a professional, well-known golfer as well as a suffragist. She was active in the women’s suffrage movement through the early 1900s, and was arrested along with several other women multiple times throughout 1917-18 for picketing the White House and protesting at other office buildings and landmarks.

Her mother, Lily Burchell, was a well-known golfer and Daughter of the American Revolution member and her father, John E. Greiner, was a famous engineer, making them prominent figures of Baltimore society. Gladys Greiner often competed in golf tournaments against her mother, losing the state title to her in 1921 but earning redemption in 1922. Contention between the mother and daughter pair, however, transcended their athletic sparring.

Due to her actions and support of women’s suffrage, Greiner’s relationship with her parents seems to have been somewhat troubled. In fact, January 4, 1920 they released a public statement in the Baltimore Sun emphasizing her intelligence and self-respect while at the same time renouncing her actions and any purported ties to radical politics. The content and tone of their statements reveal the rather public contempt Greiner’s parents held for her political views. While they maintained that she broke no laws in her picketing, they also portrayed her as wrongheaded and silly, caught up almost unwillingly in the current of the suffrage movement. The statement John E. Greiner released to the press on behalf of his wife and himself both distanced the parents from their daughter, but also made sure to distance all three from socialists, Bolshevists, and communists–all dangerous views to be associated with at the time. Though this by no means excuses the statement, perhaps the parents were trying to shield themselves and their daughter from the political backlash that was associated with having such views around the time of the first Red Scare.

Gladys Greiner’s involvement with the National Woman’s Party started making headlines when she first was arrested in June 1917 with Mrs. Lawrence Lewis for picketing outside the White House. The following July 4th Greiner was arrested again, marching with her sisters, and was sentenced to three days in District jail. In early October, Greiner picketed outside the Senate Office Building with the threat of arrest looming. On October 20, 1917, she was arrested alongside Alice Paul and other suffragists for picketing outside the West Gates of the White House. This time she was sentenced to 30 days in prison, where she staged a 67-hour hunger strike. When interviewed by the Baltimore Sunabout this particular imprisonment, Greiner stated:

“I was discriminated against from the moment I was committed to the jail. In fact, all the suffragist prisoners are discriminated against and refused the privileges granted the ordinary inmates. All others received visitors, but not the suffragists. I saw none during my entire time in jail. Even my minister was refused admittance. I had no change of clothing while I was in jail. They refused to bring me my bag from the office. They put me in solitary confinement because I broke a window to get some fresh air, and they were so anxious to get rid of me that they gave me five days off for good behavior.”

Another noteworthy arrest came in August of 1918. As a group from a march of over a hundred women broke off and began protesting at the base of the Lafayette statue, Greiner and 46 other women were placed under arrest. During these trials, the women chose to represent themselves, refusing to acknowledge the legitimacy of the court. Fellow suffragist Hazel Hunkins defended their tactics saying, “Women cannot be law-breakers until they are law-makers.”

In 1919, Greiner participated as part of the “Prison Special” tour. The previously imprisoned suffragists wore prison clothes and retold their experiences in prison to garner support for a federal suffrage amendment. On the Democracy Limited train, Greiner traveled from Washington, D.C. to Charleston, Jacksonville, Chattanooga, New Orleans, San Antonio, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Denver, Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, Syracuse, Boston, Hartford, and New York. By August 18, 1920 the 19th Amendment was ratified granting women the same right to vote as men held.

In the early 20’s (likely 1923), Greiner was elected treasurer of the NWP. She continued her activism, focusing on the labor movement. Gladys Greiner passed away at the age of 70 in April 1961 and is buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore.

Gladys Greiner’s birth and family information can be found at http://www.genealogy.com/ftm/f/o/s/William-Foster/GENE10-0023.html.

Quotations and information regarding her arrests and familial relationships are available in the Baltimore Sun archives at http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/docview/534796076/30A56472F3244943PQ/110?accountid=14696and http://search.proquest.com/hnpbaltimoresun/pagepdf/537374546/Record/30A56472F3244943PQ/22?accountid=14696 .

In Doris Stevens, Jailed for Freedom (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920) you will find the arrest record for Miss Greiner (p. 360) as well as a photo in the section that precedes the book’s appendix.